Imposter Syndrome: When Success Hides Fear

Many of us are familiar with the feeling of doubting our abilities, even if we have achieved significant success. This … Read More

Tel/Whatssap (+34) 678222694 | Email: natalia@nbelousova.com

Many of us are familiar with the feeling of doubting our abilities, even if we have achieved significant success. This … Read More

➡️ So, in order to get out of the role of a victim, you should stop complaining or wait for … Read More

Many of us are familiar with the feeling of doubting our abilities, even if we have achieved significant success. This is impostor syndrome—the feeling that we don’t really deserve our achievements, or that we will soon be exposed as a “fraud.” The arguments usually include phrases: “I was just lucky,” “I was in the right place at the right time.” This is how a person tries to distance himself from his success, because he does not believe that he is capable of something like that.

This internal conflict can undermine self-esteem and interfere with professional growth. But remember, you are not alone in this! Many successful people have experienced or are experiencing this syndrome.

If you are..

-️You feel like a pretender

You believe that you do not deserve the success or position you have achieved. You’re afraid that one day everyone will realize how incompetent you really are. The result is meticulous perfectionism, fear of making mistakes, and even fear of success.

-️You explain your success by luck or other external reasons, but not by your work or abilities. And at the same time you are afraid that next time you will not be lucky.

-️You devalue your success

You believe that the task completed was too easy and does not deserve much attention.

…You most likely have impostor syndrome!

For a more accurate determination, take the test:

Imposter syndrome can be contrasted with the Dunning-Kruger effect – a phenomenon in which people with a low level of competence make professional mistakes without realizing them at all. As a result, inflated ideas about one’s own importance and abilities. Simply put, this is false confidence in one’s own professionalism. Such people are called differently: amateurs, lamer, etc.

7 Steps to Overcome Imposter Syndrome:

To objectively evaluate your successes and gain more confidence in your abilities, you need to learn how to track your progress.

Throughout our lives, we constantly see dreams: pleasant and scary, sad and joyful, fantastic and ordinary. But almost no one thinks about the fact that any dream carries with it the opportunity to learn a lot of interesting and useful things about oneself, to bring into consciousness what is hidden in the depths of forgotten memories. A dream, as a rule, contains numerous metaphors and images that will help reveal unconscious needs, answer questions that interest us, see our personality in a new light and connect the disparate parts of our “I”.

It is advisable to start every morning by remembering your dreams. Having caught on to any detail, you can unravel the threads of seemingly lost images, and subsequently restore most of the dream. After reproducing the dream in memory, you need to pay attention to the most intense images that evoke an emotional reaction. Next, you need to enter each image as fully as possible, merge with it, and feel like a character in your dream. Become a monster that chases you or a stranger, an old broken car that you remember strongly in a dream or an abandoned house that has become rickety from time to time. Go through any detail that attracted attention or caused disgust/fear/joy, that is, any object with emotional overtones. When reproducing your dream, try to feel, without words, this or that image.

Remember what interested you in the coming days; often a dream contains something that was missed, forgotten, something that you need to realize and make into your life experience. It is important to remember that analyzing and mentally analyzing dreams gives only minor results and leads to further illusory constructions that confuse you even more. It is much more effective to relive your dream, consciously, noticing any reactions you have to it.

Any character in your dream is part of your personality. Bad, angry and scary images often represent the manifestation of rejected parts of the personality. Suppressed anger or resentment, traumatic memories and much more that you have discarded as negative are reflected in the form of dreams. The internal struggle that increasingly accompanies a person throughout life leads to the suppression and repression of certain aspects of our “I”. Everything that is assessed as negative or undesirable and is subsequently repressed from consciousness weakens and divides us. For example, if we cannot experience and recognize our anger, calling it unacceptable for a “cultured” or “kind” person, we become more vulnerable. Anger, in turn, is either a reaction of adaptation to unexpected events, or an unconscious fear for one’s life or an illusory image that most of us diligently maintain in front of others. Rejecting any feeling, considering it bad, we are divided into several independent parts: one of which experiences this feeling, the other denies or blames itself for its manifestation. Thus, the internal struggle increasingly splits us into many opposing personalities, into different “I”s, which from time to time take power over us. One way to regain integrity, calm and confidence is through dream integration. By remembering and experiencing our dream, turning into negative and positive characters, into details of the situation and entire buildings, into various objects and vague images, we will be able to bring internal conflicts to the light of awareness and resolve them. By becoming conscious of dreams, we discover, step by step, new facets of our inner world. After all, every piece of sleep expresses our complex, fragmented “I”. By simultaneously perceiving two parts of our personality fighting each other, we bring them to integration, merging into one stable entity. By considering your dreams as metaphors, it is possible to discover long-forgotten desires, memories and unfinished business that drain vital energy from us and that do not allow us to live a harmonious and happy life.

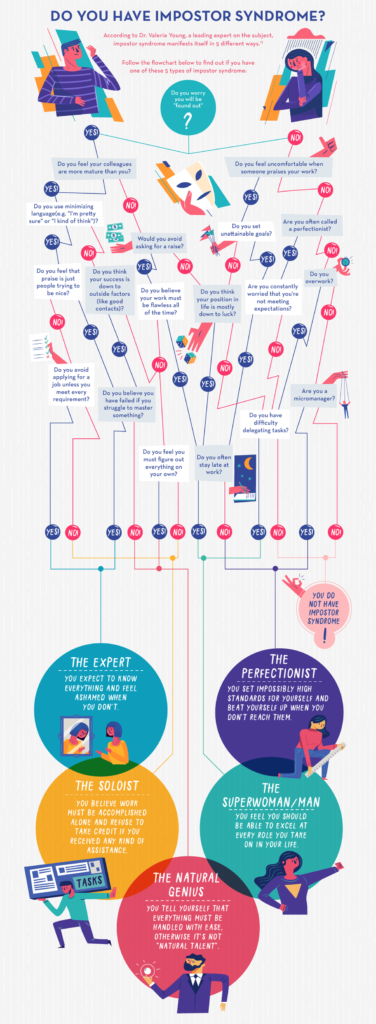

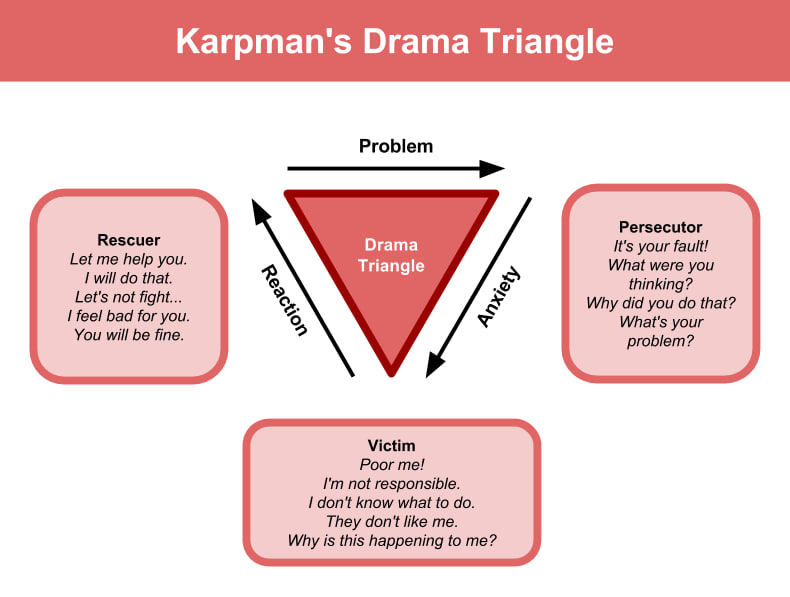

➡️ So, in order to get out of the role of a victim, you should stop complaining or wait for salvation, develop the skills of confident behavior, and internal strong adult support. It is also very important to be able to show aggression, say “no” and defend your boundaries, because the main feature of the sacrificial position is the suppression of anger and aggression. If you recognize yourself in the role of a victim, stop for a second and think: “Why am I choosing this again now? Will what I receive compensate for my energy and physical costs?

➡️ Developing empathy, respect, and the ability to hear the point of view of others will help change the role of the aggressor. If you recognize an aggressor in yourself, ask yourself questions: “Who am I teaching? Is everyone really stupid, and I’m the only smart one?” Give others the opportunity to live their lives. Work through your aggression, perhaps as a child you were subjected to physical and psychological violence and this is a consequence of your behavior. Learn to negotiate. They are more effective than humiliation.

➡️ To stop getting involved in the Karpman triangle through the role of rescuer, stop giving unsolicited advice

and work through the fear of being unwanted. Just ask others questions: “What kind of help do you need and do you need it at all? How can I help you? Do you need my advice or something else…?”

Rescuers should realize: everyone must go their own way through their own mistakes. Therefore, do not impose yourself if you are not asked. Learn to feel your boundaries and the boundaries of other people. Keep yourself busy with interesting things and then you won’t have the need to participate in other people’s “series.” Learn to be needed by yourself, and then there will be no need to gain a sense of your own need by “doing good.” None of the “players” in Karpman’s triangle develops as a person, but simply moves from role to role. To get out of this triangle, you first need to realize your role and stop yourself several times a day and ask the question “why am I doing this now?”

1. Establish trust.

2. Briefly define the goals and objectives of counseling.

3. Identify and adjust client expectations from counseling.

4. Motivate the client to cooperate with you.

5. Encourage the client to tell a detailed story about the situation that brought him to you:

• listen to the client’s presentation of the problem;

• determine the locus of the client’s complaint (what, who is he complaining about);

• help the client adjust the formulation of the problem if, in his presentation, it is insoluble or its solution depends entirely on other people;

• specify how long this problem has existed;

• identify the impact this problem has on the client’s life;

• ask how he feels about this problem

6. Help the client understand his contribution to the problem.

7. Help the client clearly articulate his difficulties.

8. Come to an understanding with the client about what exactly their problem is and how you can help resolve it.

9. Desired changes:

• help the client understand what exactly does not suit him in the current situation and what exactly he wants to change;

• adjust the client’s expectations if they are unrealistic and do not concern changes in oneself or one’s own relationships with someone or something, but are related to other people;

• identify markers by which the client will understand that the desired changes have occurred.

10. Alternative ways to solve the problem:

• help the client formulate different ways to solve the problem;

• find out which method is the most appropriate;

• create an experimental situation in which the client could try out new forms of behavior.

11. Search for resources:

• ask the client about his strengths, capabilities and potential;

• find out from the client how he overcame similar situations and what personal resources he relied on;

• Discuss with the client ways in which he can get support.

12. Eco-friendly check:

• find out what was new for the client during the consultation;

• clarify (if this is not the first consultation) whether anything has changed in the client’s life after your work;

• ask if the client behaves differently as a result of counseling;

• find out what exactly he is going to do today, tomorrow in order to implement what he decided to do during the consultation; • find out at follow-up meetings what the client has done from the planned program of action and support him in those areas where positive changes are observed.

Michael Balint is a Hungarian-British psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and psychotherapist. Specialist in group psychotherapy and group psychoanalysis. Founder of the Balint groups.

This method of group training research work was named after its creator, who, since 1949, held discussion group seminars with practicing doctors and psychiatrists at the Tavistock Clinic in London. The experience summarized by Balint in his book “The Doctor, His Patient and His Illness” formed the basis for the method of conducting research and training seminars. The central object of study in the classical Balint group is the doctor-patient relationship. The patient transfers to the doctor certain attitudes, emotional and behavioral stereotypes that are similar to his attitude towards the objects of his real life (significant persons in his immediate environment). Analysis of these relationships makes it possible to more fully understand the patient in all the diversity of his connections and interactions with the real world, which helps to increase the effectiveness of therapy.

Balint saw the objectives of the seminar sessions in the analysis of relationships in medical professional practice, the development of diagnostics of relationships, comprehension of the true needs of the patient, and a deep understanding of the disease.

At the moment, Balint groups are an effective method of increasing professional communication skills of specialists in helping professions, reducing professional stress and “emotional burnout”, understanding the problems of the patient/client and the difficulties of communication with him, awareness of the therapeutic significance of interpersonal relationships and their boundaries, awareness of one’s own “blindness” spots.”

Balint group classes are conducted in several stages or “steps”.

The first “step” can be conventionally called “identifying the customer.” The lesson traditionally begins with the facilitator’s question: “Who would like to present for consideration their own case, a problem that creates a state of discomfort?”

The second “step” is the “customer’s” story about his difficult case from practice. The leader and group members listen carefully. Their observations can be very useful for subsequent analysis of the speaker’s communication difficulties.

The third “step” is for the “customer” to formulate questions for the group based on his own case. At this stage, the facilitator helps the “customer” formulate requests (questions and wishes) to the group, which contain a desire to receive new knowledge, feedback and (or) group support. It is advisable to write questions on the board or tablet, because… all group members refer to them constantly, maintaining the accuracy of their content.

The fourth “step” is the group asking questions to the participant who presented the case. All spontaneous reactions of the participants, their behavior and emotional manifestations are recorded by the presenter and can later be the object of dynamic analysis.

At this stage, the “customer” is often surprised to discover that for some reason he forgot or did not take into account very important aspects of his case. Many unconscious moments become clearer for him.

The fifth “step” is the final formulation by the “customer” of the issues that he would like to bring up for discussion. Sometimes the wording of questions is retained in its original form. More often, however, they undergo changes. Some of the previously posed questions may even lose their relevance for the “customer”, thanks to his awareness of a number of points at the previous stage.

Often an additional question taken by the “customer” is the question of what aspects in the proposed case he is not sufficiently aware of, from the point of view of the group.

The sixth “step” is the group’s responses to the “customer’s” requests and free discussion.

All participants in a circle answer the surveys assigned to them. Responses may reflect the feelings of group members: “In this case, I feel like…”.

No less important than certain judgments and feedback for the “customer” and other participants may be answers like: “I also had a similar situation, and I found a way out…”. The very fact that many group members offer an identical or similar vision of his situation is of great importance to him, but the group does not seek to impose anything, realizing that the speaker can block the acceptance of information.

Free associations are also encouraged at this stage. After any member of the group has spoken, the “customer” can ask him clarifying questions if anything remains unclear. It may be that in a Balint group one participant consciously or unconsciously identifies himself with the “customer” or his “partner” in the situation under discussion. The latter’s statements could be, for example, like this: “You know, I imagined myself in place… when you said something to him, reproducing the situation, and at the same time stuttered, I felt tense.” Such statements have special value for the psychotherapist presenting the case, and for other participants as well. In a well-functioning Balint group, individual remarks provoke the continuation of the discussion in the form of further circles or a free, but correctly managed discussion. This leads to a deeper understanding of the problems, creative collective development of the voiced points of view, unexpected angles of vision of the situation under discussion.

Feedback from the group leader to the “customer” is carried out at the seventh “step”. The facilitator summarizes the group’s answers, expresses his own vision of the situation presented for discussion, assumptions about the reasons for the difficulties encountered by the “customer,” etc. At the end of the work, the leader thanks the “customer” for providing the case and the courage to analyze it, and the group members for their support of the employee.

At the eighth “step” the “customer” gives information about his feelings. His statements may relate to his own emotional state and impressions of the group’s work. He can also provide feedback to specific participants containing his opinion on the effectiveness of their activities, thank them for their support, or express their condition in words. A Balint session may end with statements from individual group members about their feelings and impressions.

Supervision – from lat. supervidere, view from above.

Intervision – from lat. inter – between, visio – vision (vision between).

Supervision and intervision are similar in many ways. These are formats in which specialists are trained in order to improve skills, increase the level of self-analysis, expand knowledge, and also get help in various situations of psychological practice that cause difficulties.

The difference between supervision and intervision is that supervision is carried out by a specialist of a higher rank. Here, vertical, hierarchical interaction takes place: supervisor-group or supervisor-individual supervisor, and in intervision this interaction takes place on a horizontal basis, between colleagues of equal status. Intervision is an “intercollegial” or “intercollegial” method of working in a group of professionals involved in counseling, therapy or treatment of clients, and is also a space for communication, exchange of experience, professional support and growth.

In intervision, the most important aspect is that group members are jointly responsible for the content of the sessions; positions in the intervision group are equal. The supervision group is a unique place where you can try yourself in different roles: be a speaker, an observer, ask for help, support, feedback, bring up a work case for discussion, share your feelings, experience, and even volunteer as a leader; The leaders in the inspection group change and are selected from the participants in the process themselves. If a therapist does not supervise/internize for a long time, he runs the risk of “getting bogged down in his countertransference,” that is, he may engage in some kind of unconscious game with his client, may experience excessive emotions towards his client, and therefore lose his working therapeutic position. No matter how prepared a psychotherapist is, and no matter how extensive his practice, he still remains a person with his own unconscious, which he cannot fully understand. By engaging in intensive contact with the patient, the therapist may, to one degree or another, lose his objectivity. This is a normal process, and this is precisely the purpose that supervision and intervision serve.

Today I conducted supervision using the AFCODEV method – Collaborative Professional Development Method, founded by Adrien Payette and Claude Champagne.

I will leave here a description and algorithm for working with this method.

“It is an approach to development for people who believe they can learn from each other and improve their professional practice.”

ADRIENNE PAYETTE, CLAUDE CHAMPAGNE, 1997

Professional co-development brings together a group of people who share similar professional interests, learn together and develop a “hive mind” through a 6-step process that structures communication, reflection and action.

Collaborative development focuses on interactions between participants.

Three roles necessary for the functioning of a professional co-development group:

The role of “client or supervisor”. He brings a problem or complexity that he wants to explore, find clues, see other points of view.

The role of “consultant or support participant.” Participates in the process of discussing and finding a solution to the client’s (supervisor) problem.

The role of the “facilitator or supervisor” is the one who leads the group through the 6 stages of the session.

1. Presentation of the situation.

The client (supervisor) reveals the situation, the consultants listen.

2. Clarification.

Consultants ask questions, the client (supervisor) answers and clarifies.

3. Agreement.

The client (supervisor) formulates his request to the group and indicates the type of assistance desired. The supervisor may ask for advice, questions for reflection, reactions, comments, ideas, suggestions, impressions, the consultants’ own ways of solving the problem, or any other interventions.

4. Consultation.

Based on the supervisor’s request, consultants analyze the situation.

5. Summary.

The client (supervisor) analyzes the information, indicates what was useful to him, and develops an action plan.

6. Summing up.

The client (supervisor) and consultants describe their findings and reflect on what they learned in the session. Evaluate the experience gained.

“Objectification” in the context of relationships means contact in which one person sees in the other not a person, but an “object”, an object for the embodiment of his own desires. Anyone who does this is in an immature position. It takes a certain degree of maturity, growing up, to begin to see people in a complex, not fragmented way.

Healthy development includes respecting others as people with their own rights, needs, limitations, good and bad traits. A man or woman who views another person as an object and looks at him solely from the point of view of satisfying his own needs is not capable of healthy, mature relationships, especially romantic or sexual ones.

People prone to objectification are less capable of empathy than others. A person who sees others holistically can look at the world through the eyes of another, notice similarities and differences with him, recognize strengths and weaknesses, likes and dislikes. These abilities determine the ability to sympathize and take another person’s point of view. It is difficult for a person who sees another as an object or function to have compassion and take the other’s place.

Objectification depends on the degree to which the child has been emotionally accepted or rejected by his immediate environment. If his needs were not met during childhood, the individual will feel insignificant, incompetent and unworthy of love. The understanding of the subject is connected by a person’s attitude towards himself as an independent, active figure.

Subjectivity is a category in psychology that expresses the essence of a person’s inner world, the possibility of creative transformation of the surrounding reality, the expression of one’s own opinion, emotions, feelings, based not on how it should be, but on how the subject himself thinks and feels.

Subjective relationships represent the interaction between people based on the recognition of each of them as an individual with their own unique needs, rights and values. In such relationships, people consider each other’s individuality and strive for mutual understanding, cooperation and respect.

Objectified relations can be compared to commodity-money relations. In such a relationship, one person views the other as an object that can be used or exchanged for something to satisfy his or her own needs, just as goods are exchanged for money. The value and significance of another person is determined solely in the context of obtaining benefits or satisfying one’s own interests. Such relationships lack recognition of the other person’s individuality, uniqueness, and rights, making them unhealthy and lacking depth.

A psychologist must have a strong theoretical foundation and understanding of psychological concepts, methods and techniques. Insufficient education or a frivolous approach to training can lead to inadequate understanding of the client’s problems, incorrect diagnosis and incompetent assistance.

Lack of supervision can result in missed valuable opportunities for learning, reflection and improvement of practice. Learning new methods and techniques, as well as analyzing individual situations with a supervisor, expands the possibilities in working with a client, allows you to avoid mistakes and correct any difficulties that arise in a timely manner.

Empathy is great, but experiencing the client’s problems as one’s own can lead to a shift in focus to one’s own experiences and limit the professional’s ability to maintain objectivity and independence in the work.

The inability to establish financial relationships with clients and working for free lead to rapid burnout, as well as a decrease in the assessment and recognition of the professional skills of a psychologist. Free, regular help also does not help the client take responsibility for the recovery process.

In the quest of a novice psychologist to radically improve a client’s life, one must always adhere to the principle of moderation and proceed from the client’s request. Setting clear and realistic therapeutic goals is an important aspect of a psychologist’s work. It is necessary to be able to listen and understand the client’s needs in order to formulate goals that will be aimed at solving the problems expressed by the client.

It is important to understand that the psychotherapeutic process requires time and gradual development, as well as systematic and in-depth exploration, working on symptoms and developing new skills and understanding. Psychotherapy can be a process spanning several sessions, several months, or even several years, depending on the complexity and nature of the client’s problem.

Failure to set boundaries can lead to a violation of ethical standards and even the creation of a dependent relationship with the client. Clear time frames for the session, a preliminary agreement on the terms of therapy, the opportunity to write between sessions – all of this helps create a clear framework in which there is clarity and safety.

Working with psychological needs implies a high level of trust and openness; the psychologist actually acts as a parent, an adult on whom the client can rely; abuse of trust causes irreparable harm to the client. The client’s romantic feelings towards the psychologist are most often due to transference. If a psychologist cannot cope with his feelings, he needs to undergo supervision and redirect the client to another specialist.

The consultant’s task is to help the client learn to make responsible decisions independently. The client will be able to come to a solution to his problem not if he receives a ready-made recipe or algorithm of actions, but will be able to identify the origins and underlying reasons for his actions.

It is important to understand that self-confidence without proper self-analysis and personal therapy can become an obstacle to effective psychological help. Regardless of experience and status as a psychologist, a professional must constantly strive for self-development.

Without self-analysis and personal therapy, a psychologist may miss the opportunity to resolve his own emotional and psychological problems, to see his own stereotypes and prejudices, which can affect his work with clients, objectivity and impartiality.

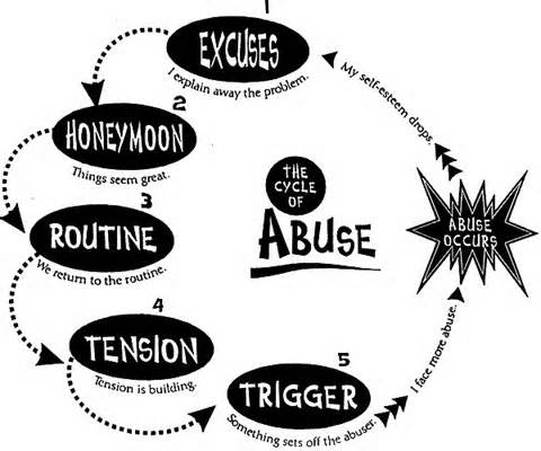

After working with clients who have survived abusive relationships, I see a paradoxical but interesting feature: people who have survived such relationships perceive negative attention as something meaningful and important. In a toxic relationship, the abuser gives mixed signals, creating a sense of intense passion and attention, even if that attention is destructive.

When such clients try to leave and create new relationships where there are no extreme displays of attention, they develop a feeling of emptiness or boredom. After all, healthy relationships are based on respect, care and mutual understanding, and do not always manifest themselves through dramatic scenarios and emotional rollercoasters.

Abusive displays of attention, although seemingly intense, actually represent a distorted view of love. They create dependence and control, emotional swings from alienation and coldness to passionate scenes. A person gets hooked on a hormonal needle. In a healthy relationship, true love is shown through respect, support and care, not through toxic drama and manipulation.

People who experienced neglect and attachment trauma in childhood did not receive the emotional support and security they needed from their parents or caregivers. This results in an unstable attachment pattern where they seek comfort, validation and support in relationships but have difficulty setting healthy boundaries and recognizing their needs.

This has a huge impact on their understanding of love and affection in adulthood. They may end up in abusive relationships by seeking the same form of attention they received as children. Sometimes they may even justify their partners’ negative behavior as a sign of care or attention, because that’s the only thing they’ve ever known. Due to the lack of healthy models in childhood, they may not recognize warning signs or succumb to the feeling that this behavior is normal. The world is becoming upside down, concepts are being replaced. When the only form of attention available in childhood was through criticism and negativity, children grow up accustomed to the fact that yelling, devaluation, or even physical assault is better than complete indifference.

The person may begin to doubt themselves, feel that they deserve such treatment, or that they are not capable of healthier relationships. Moreover, abusive relationships can be both emotionally toxic and physically draining. Often, a person in such a relationship may feel constant stress, anxiety and worry, which leads to emotional and physical exhaustion, and constant retraumatization.

If you recognize yourself, it is important to remember that it is not your fault, but your responsibility. What can you do about it to improve your quality of life and relationships in the present?

Working on yourself and seeking help in therapy can play a huge role in re-evaluating your beliefs so you can set new, healthy boundaries for yourself and attract positive, supportive relationships into your life. This is a difficult but important step towards breaking free from stereotypes and building a healthier future.

Breaking free from such relationships can be a difficult but important step toward rebuilding your self-esteem and regaining emotional stability. The process begins with recognizing that the relationship is harmful and seeking support—whether through friends, family, or professionals. Gradually, through working on yourself and your environment, you can begin to restore your self-esteem and believe in your own worth.